How do things currently stand when it comes to gender equality in finances? Not good. Throughout their lives, women only earn around half of what men do. And that is leading to a high risk of poverty. A glimpse at the figures and how they are calculated.

Just imagine you start a new job on 1 January. It’s fun, you feel comfortable there, everything is great. The only drawback: you only start receiving your salary from 8 March. Before that you are working for free. Sounds unfair? That’s because it is. And that is exactly the case, if the gender pay gap between men and women in Germany is anything to go by. The gap currently stands at 18%.

Equal Pay Day, which is taking place on March 7 this year, symbolically marks the day of the year until which women work for free, while men have been paid for their work since the beginning of the year.

The good news is that in the past year the pay gap was 1% higher, which means that some progress is being made. But looking back at the last 15 years, we can see that things are still moving at a snail’s pace.

Gender pay gap: How is it calculated and why?

It’s important to know that there is a difference between the unadjusted and the adjusted gender pay gaps. The unadjusted pay gap is 18%, the adjusted 6%.

The unadjusted gender pay gap of 18% compares the average earnings of all employees. And the pay gap varies from region to region: in the east of Germany, it’s a lot lower than it is in the west.

The adjusted gender pay gap takes into account the salaries in comparable positions, carrying out comparable tasks, which makes it a direct comparison of industries and jobs. Here the gap is 6% – although women are usually better qualified than men these days.

The adjusted gender pay gap – is it really that bad?

So if the adjusted value is “just” 6%, is the pay gap really such a big deal? Let’s do a simple calculation: if a woman earns 6% less than her male colleague in exactly the same position, that works out as €150 a month less that she would be earning if her male colleague was earning a monthly salary of €2,500. That is equivalent to almost €2,000 a year, which, over five years, would amount to almost €10,000 that she would be missing out on. So it might not sound like very much, but it actually is.

The unadjusted gender pay gap gives us more of an insight into the equality of women and men in our society. That is because it highlights structural inequalities, such as the lower paid typically female professions in childcare and caregiving, for example, but also the high number of women working part time. Both factors lead to financial challenges, the impact of which we cannot overlook as a society. So, let’s take a look at some other figures that are important in this context.

- Image 1

Why wage equality comes down to more than just a monthly salary

The financial imbalance between women and men increases from the age of 30 and has much more of an impact than merely slightly lower wages each month. And this continues throughout life, all the way to retirement and pension age. The circumstances are therefore often closely interlinked:

Almost half of all women (47.9%) work part time. And only around one in ten men. Around half of women make this decision because of family commitments. So what does that mean for women’s wage development?

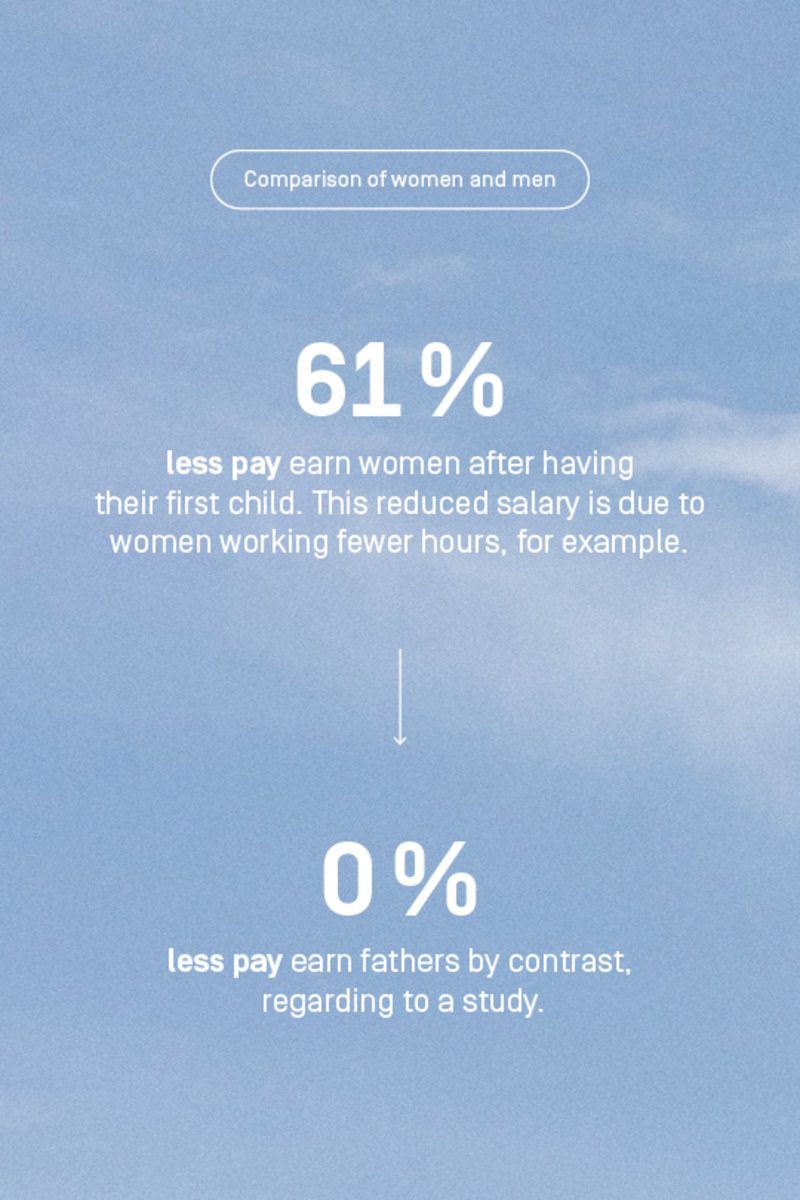

A study showed that after having their first child, women earn 61% less pay, while fathers experience no changes to their salary at all. This reduced salary is mainly due to women working fewer hours, but also because they have fewer promotion opportunities. And the first two points bring us straight on to the next…

The Gender Lifetime Gap is 45% in the West and 40 in the East. That means that women only earn around half of the income that men do throughout their lives. Which brings us on to our next topic…

The pension gap is 46%. That means that women only receive around half of the pension that men do. On average, women receive around €700 a month, which is resulting in old-age poverty. Incidentally, that is the highest pension gap of all OECD states in Europe. But poverty looms even before that: usually when the decision to start a family is made. This leads us to our next point:

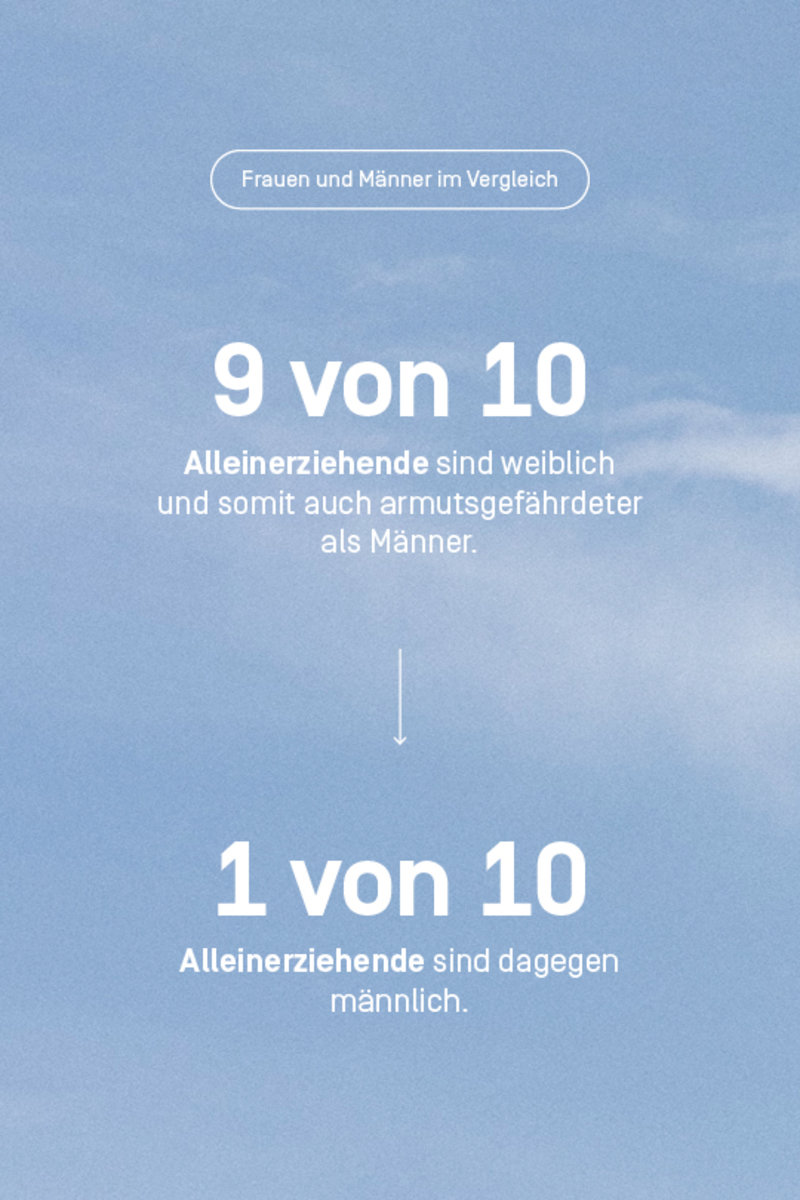

Overall, women are a lot more at risk of poverty than men, as single parents, for example, who in nine out of ten cases are female. But other issues such as childcare options, part-time work and a lack of promotion prospects also play a role here.

Would it help if more women were to take on male-dominated jobs? Well, yes and no. Yes, because of course that would increase their wages – and technical professions also offer good future prospects. But a study that examined salary developments over a longer period showed that steering women into sectors that have paid well in the past is not necessarily a solution. Because, as the data shows, when the quota of women employed increased to over 60%, their wages decreased. That effect also worked the other way around. In the 1960s, for example, the programming sector was dominated by women – but when men started taking over, the pay increased.

Something else that these figures show is that the gender pay gap is, in many respects, not a gender issue, but a family issue – because it often has a lot to do with the family situation and the fact that women in relationships, or single mothers, often take on the lion’s share of unpaid domestic and caregiving or child-rearing work at home. Which means that the repercussions of unpaid work affect mainly women. So, what will help us to make progress when it comes to the gender gap? Recognizing that it exists in the first place. It exists, it is real and we shouldn’t just be looking at the adjusted figure of 6%, but also addressing the structural inequalities.

Measures that could help to close the gender pay gap:

Helping employees to balance work and family life can therefore have the most positive impact. And it would help if parents were able to share the caregiving duties of their children or elderly family members more equally, if childcare facilities were significantly developed and if full-time positions were reduced to under 40 hours a week. Making it possible to have a career on part-time hours would also help to close the gap. Raising the wages of essential workers, i.e., those working in jobs that are so important to society, such as caregivers and teachers, would also be an effective tool.

Introducing tax incentives for more working hours is another option, because due to the German government’s current policy of tax splitting for married couples, it’s not often worth both partners working full time. But if we look at the divorce rate in Germany, it soon becomes clear that we cannot rely on marriage to give us financial security.

Improving transparency can also help to close the gender pay gap because this makes it easier to compare what your colleagues are being paid and will make sure that you don’t sell yourself short during salary negotiations with your boss. There are many ways that we can close the pay gap.

Whichever approach is taken, one thing is clear: closing the gap would bring so many positive effects. But if we want to achieve equality, the most important thing is to start ensuring that neither a person’s gender nor their family situation have a negative impact on their financial security or how they are appreciated in the workplace.

Find out more:

Find out further figures on the topic of old-age poverty among women here.

Here you will find our guide with lots of tips about money in relationships.

And here are some ideas on how you can achieve financial independence.